Waste myth #5: Landfill levies don’t affect behaviour

By Mike Ritchie, Director, MRA Consulting Group

70% of the growth in recycling in the last 20 years is explained by the rise in landfill levies. Levies do change behaviour, by making recycling a cheaper option than landfill.

This article tries to explain the role and contribution that the landfill levies make to resource recovery.

Let’s start with the basics- What is a landfill levy?

It is a State government tax paid by you and I on waste we landfill. Each time a tonne of waste goes over a landfill weighbridge, there is a tax levied on the waste. The landfill operator pays the levy to the State government if they landfill that waste. (They do not pay it if they recycle that material and divert it before the hole in the ground).

The levies vary between States as set out below.

| State | Metro Levy 22/23 | Rural levy22/23 |

|---|---|---|

| NSW | 151.6 | 87.3 |

| QLD | 95 | 88 |

| VIC | 125.9 | 62.95 |

| SA | 149 | 74.5 |

| WA | 70 | 0 |

| TAS | 20 | 20 |

| ACT | Only for commercial loads, incorporated into the $179.20/t fee | |

| NT | 0 | 0 |

The levy is added to the normal cost of operating a landfill and therefore push up the “gate fee” that you and I, Councils, businesses etc pay to dispose.

As such they make landfilling more expensive relative to the alternatives (separation, reuse, recycling etc).

The role of the landfill levy.

Landfill levies have two primary purposes.

1. Changing the relative costs of landfill and recycling

Firstly, they raise the relative cost of landfilling and drive behaviour change in favour of recycling. More materials are recycled because landfilling costs more.

Australia and particularly rural regional Australia, is still characterised by cheap (under-priced) landfill. Very few landfills include the costs of post closure remediation and monitoring (40 years) or the cost of asset replacement (buying a new property or quarry to build the next landfill). Almost none incorporate the costs of methane emissions on climate change. Many don’t even meet their full costs of operation.

That is one reason that we still landfill 40% of the materials generated by the economy as “waste”. This is particularly true in regional Australia and for mixed waste streams.

Recyclers compete with landfill for materials. Higher landfill gate fees (driven by levy increases), allows recyclers to compete for access to recyclable materials (material processing for resource recovery is costly).

Most people in Australia do not realise that recycling is in direct competition with landfill for access to materials. Changing that economic balance is the key role of the levy.

2. Funding and hypothecation

The second (and lesser) role of the levy is a mechanism to raise funds for government and for grants/subsidies that support business and innovation in recycling.

Interestingly, the rate of hypothecation (dedication or pledge for waste projects) of levy funds is the most controversial aspect of the levy. Payees want more of the levy back than governments (Treasury Depts) generally want to give up. Fair enough.

The average hypothecation rate to direct recycling initiatives is about 30%. The other 70% is spent on supporting EPA’s, Departments, and other government programs (think schools, roads and hospitals).

The rate of hypothecation also varies greatly between States.

The key point is that the higher the hypothecation rate (to grants etc for waste infrastructure and programs), the sooner we get Australia on a more sustainable resource path. But to be clear grants don’t change the operating costs or profitability of recycling businesses very much. Their main effect is to bring forward investment to now, that might have occurred later.

Reminder – While levies provide funds for infrastructure and programs, their key benefit is to make more recycling commercially competitive with landfill. They let the market compete, innovate and recover materials back to the productive economy without it being sucked away by a cheap landfill.

Supporting recycling

There has been a lot of soul searching around the demise of recyclers including RedCycle in recent times. RedCycle was an innovative soft plastic collection system (via Woolies and Coles), but it suffered from unstable offtake arrangements and reuse opportunities (at the right price). These cases prove a number of things:

- It is hard to compete with cheap landfill for low value recycling streams such as soft plastics (84% of plastic packaging goes to landfill);

- It is expensive to collect, sort, wash and process recyclables (recyclers need a decent gate fee);

- Recycled products need viable and continuing markets or offtake (recyclers need minimum recycled content rules);

- Collection is not recycling (recyclers need to build reprocessing infrastructure that is profitable).

It is easy to recycle some streams such as aluminium. It is ubiquitous, valuable ($1,500/t) and has strong end markets.

That is not true for many things we need to recycle – mattresses, soft plastic, polystyrene, timber etc. The economics is often marginal at best. That is why companies go broke.

A higher landfill price allows recyclers to charge a higher gate fee (more revenue) for the same recycling activity and reduces their dependence on end markets (somewhat).

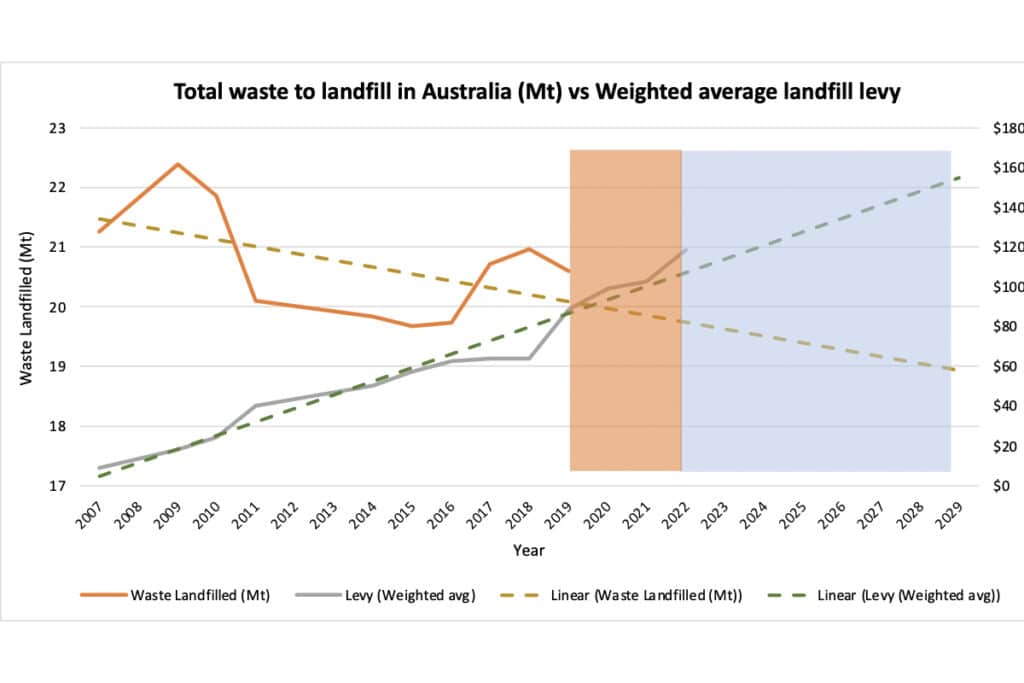

A higher landfill levy underpins their recycling business model. This is supported by the correlation observed when plotting total waste to landfill in Australia against the weighted average value of the landfill levy for Australia. Given that not all States have a levy, the downward trend of waste to landfill is quite impressive.

So why don’t we have higher levies?

The main argument against levies is that it is another tax, and we hate taxes. Fair enough.

But if governments must raise revenue via taxes, my argument is that it is better that they be progressive taxes that support the economy and improve sustainability, than regressive taxes such as payroll tax, which taxes employment or stamp duty which taxes housing.

Tweet

The tobacco tax is the best-case study I can think of. Higher tobacco tax drove a significant reduction in the consumption of tobacco (much more than just education did). The market signal worked.

People often ask, “But will government reduce other taxes in line with increases in landfill levies?” The short answer is, they should. Governments have a tax revenue requirement. Better they raise revenue via a landfill tax than payroll or stamp duty.

Local government have historically been antagonistic to landfill levies because they feel it is a tax on their landfill activities. A couple of points on this:

- 70% of all landfilled waste across Australia and therefore payment of the landfill tax, is paid by private companies not local government or householders. They generate 70% of the waste that is landfilled;

- Even if local government owns the landfill, most of the levy cost is paid by private companies not residents (think Coles, Bunnings, Seven Eleven etc); and

- Local government has been a beneficiary of grants and subsidies. A higher level of hypothecation will deliver more money back to local government.

Tasmanian local government took a mature view toward levies. Firstly, they acknowledged that higher landfill levies were inevitable given government commitments to circular economy and the 80% diversion from landfill target included in the National Waste Action Plan. So Tasmanian local government supported the introduction of a levy subject to agreed hypothecation rates. Good outcome for all.

Why a landfill levy?

We now know that landfill levies have driven most improvements in recycling in the last two decades. In 2020, the NSW Auditor General Margaret Crawford, undertook a performance audit on the Waste Levy and Grants for Waste Infrastructure, concluding that There is evidence that the waste levy has a positive impact on recycling.

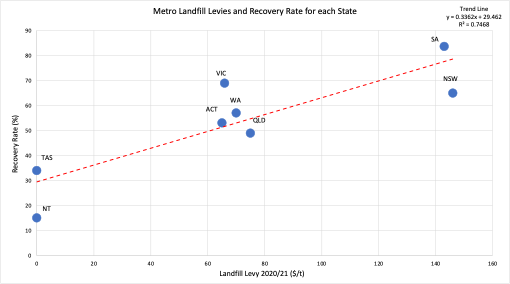

The next graph shows the relationship between levies and recycling rates across all States and Territories. Levies explain over 70% of the differences between States (R2= 0.75)

That is not to diminish other initiatives but to emphasise that if we want to shift the dial, we need to strengthen levies.

Our national target is 80% diversion by 2030. We are currently at 60%.

We have done all the easy and even some marginal recycling. But getting from 60% to 80% will be very hard. Companies will try and many will go broke because they are at the edge of viability. We need to make them less vulnerable.

They need to earn reasonable profit to be able to withstand the normal ups and downs of business.

Governments have 3 levers:

- Bans and mandates

- Levies and other price signals; or

- Education.

Either 1 or 2 will work. Education in the absence of 1 or 2 will not get us there.

Bans and Mandates

Various governments have started on bans and mandates. The NSW government has mandated commercial food collections by 2025 and household FOGO by 2030. Well done NSW.

States have started banning problematic single use plastics etc., but these are not enough or ubiquitous enough.

Mandates and bans need to be massively ramped up.

As an example, all of the Extended Producer Responsibility schemes in Australia (think TVs and Computers, Container Deposits, Tyres) currently recover less than 5% of waste materials.

To achieve the targets, we need to recycle an additional 18mt/year every year by 2030.

I am fine with governments lining up a big, long list of products to ban, or mandate recycling thereof, but to achieve the targets it will be a long list and require massive government effort. The politics will also be hard.

Levies

The alternative is to keep increasing the levies. All recycling will become more viable with higher levies. “All boats rise in a rising tide”.

The weighted average levy price in metro cities in Australia is $105/t. This compares to European levies (in $AU and adjusted for inflation since 2021 publishing date) of: Belgium $200; UK $188; Austria $148. The penalty rates for exceeding allowable landfill rates are even higher: Northern Ireland $381; Wales $381 and Scotland $286). These are on top of landfill operating costs.

The one thing about rising landfill levies is that we won’t know in advance which companies will do well and which will not. But most recyclers will benefit. That includes landfill owners who build recycling facilities on their landfill.

There are a few levy implementation issues worth discussing:

- Bona-fide recyclers should get a discount on the levy costs they pay i.e., their residual waste that needs to go to landfill. For example, MRF operators receive 10% contamination on average and all of that needs to go to landfill at present. That is a drag on profitability. Rather than penalising bona-fide recyclers we should discount their levy by say 50%. We do this now for metal recyclers.

- Governments should announce levy increases as far into the future as possible. This forward announcement will allow businesses to bring forward investment based on where the levy will be in the future. That accelerates investment.

- Local government should coordinate levy changes with Government to secure decent hypothecation rates for any increase. My view is that this could be near 100% of any increase.

Conclusions

- We need to massively improve recycling to achieve our emissions and waste targets;

- Only bans, mandates or levies work at the scale we need;

- Levies drive behaviour and support recycling;

- Levies are 100% avoidable- just recycle;

- Local government can be a significant beneficiary with decent hypothecation;

- Levy funds should be spent on infrastructure, services and market development; and

- We should announce increases early to bring forward investment.

Think about it. If you agree, tell government.

Mike Ritchie is the Managing Director at MRA Consulting Group.

This article has been published by the following media outlets: