State of waste 2019

By Mike Ritchie, MRA Consulting Group

The Australian Commonwealth has achieved a first. A Minister for Waste (and Environmental Management) was announced by the Morrison Government. In the 200 years since colonial settlement we have not had a Minister with Waste in their title. I hope that ushers in a period of attention and reform.

After the China National Sword import restriction on Australian recyclables, the return of container loads of recyclables, the massive success of “War on Waste”, the 60 Minutes “expose” of waste management activities and a Four Corners documentary, waste is finally attracting attention (not all of it good). The recent collapse of SKM, one of Australia’s largest recyclers, should be focusing a lot of minds.

The increased profile will only be a positive if it generates rapid action and policy reform.

Australia has a mixed record on waste and recycling. On the positive side we have grown our recycling rate from 7% in 1996 to 58% in 2016/17. That is pretty impressive given that we don’t have a domestic Energy from Waste (EfW) industry, which tends to boost the (often over 90%) recycling rates claimed by European countries. We have a robust kerbside recycling collection system for households and the essence of good practice in the commercial, construction and demolition sectors. But our policy settings are weak compared to Europe and are not strong enough to achieve even the existing State Government targets (which themselves are relatively weak).

In fact, in 1996 Australia landfilled 21Mt of waste. In 2019 we still landfill over 21Mt of waste[1]. All of our recycling effort has been taken up by the growth in waste generation (driven by increased per capita consumption and population increases) such that we have made few in-roads on actually reducing waste to landfill.

Tweet

I am optimistic that with Commonwealth Government involvement we will see a re-emergence of a policy reform agenda and coordinated approaches to national waste and recycling.

Here are some key issues which must be addressed if we are going to create the Circular Economy that (almost) everyone endorses:

Market Price Signals

There is a significant failure of recycling and waste economics in Australia. The fact is almost all recycling in Australia is subsidised by someone. Only the metals (steel and aluminium) and fibre (paper and cardboard) have sufficient economic value to recycle themselves. In other words, the value of metal and fibre outweighs the costs of collecting and reprocessing it. All of the rest of the materials we recycle are subsidised by someone. Think kerbside recycling (subsidised by ratepayers essentially paying for collection and MRF gate fees), food waste (subsidised by waste generators), container deposit schemes (subsidised by drink consumers) etc. The bottom line is that if we want higher recycling rates then that comes at a cost to the economy and at a cost to someone. The question is who should pay and how much?

Secondly and self-evidently, waste is something that is discarded or unwanted. So, it will naturally trend towards the cheapest point of disposal. As I often say in public presentations “Waste is like water, it will flow downhill – in this case to the cheapest price”. That is a fundamental law of waste policy. If your recycling option costs a dollar more than the cost of landfill, then the waste will go to landfill (with the minor exception of companies that are prepared to voluntarily subsidise the recycling for environmental good, brand or other commitments).

Which brings me to the role of government. Only governments can remedy market failures. Single companies can’t do it. You and I can’t do it as individuals or consumers. (That doesn’t stop us trying). Governments must create the market conditions for recycling to be viable both environmentally and financially. Governments set the targets for waste diversion from landfill. They need to give the market the right signals to achieve their own targets.

Most of the 21Mt of waste that currently goes to landfill is not financially viable to recycle under current policy settings. Innovation alone won’t fix our waste market failures. The cost impediment is just too high.

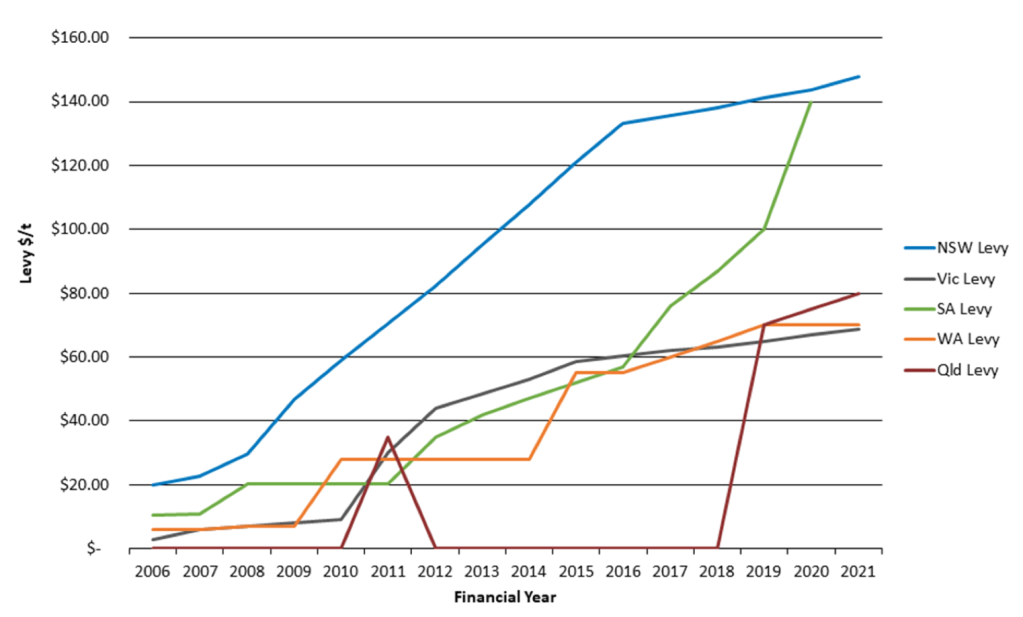

Hence governments have to intervene. To their credit most State governments have introduced landfill levies to start rebalancing the market prices, advantaging recycling over landfilling. They use some of the levy money to further subsidise new infrastructure and services. All good. But so far, not enough to drive overall waste to landfill downwards (significantly or rapidly).

If Governments don’t want to use market price signals then the only other structural policy lever is to regulate waste by requiring it to be recycled, banning it from landfill or requiring processing. That is the European model and explains much of their higher recycling rates (along with EfW).

For example, unprocessed organic waste is banned from landfill in Europe. It must be reprocessed into valuable products – compost and energy. Generating investment and jobs.

Infrastructure Funding and Planning

If we want more and better recycling then not only do we need the policy incentives for companies and councils to invest in it, but we need them to be able to get bits of infrastructure approved and built. That is inherently difficult for waste infrastructure.

Nobody wants a waste processing plant, a transfer station or a composting facility next door to them. Many councils are responsive to local community concerns. Fair enough. But what that means in practice is waste activities are either being prohibited or pushed further and further away from waste generators (to the city outskirts) increasing traffic and heavy truck movements.

Clearly what is needed in all States is a planning policy statement that preferences waste infrastructure in industrial zones and has an approvals pathway that recognises the strategic importance of waste assets. In NSW for example the industry has been calling for a SEPP (State Environmental Planning Policy) for waste infrastructure. If we don’t have the kit then we can’t recycle the 21Mt of mixed waste that is currently being landfilled.

Finally, on infrastructure (large and small) we need to preference the building of kit to process mixed materials; MRF, C&I sorting platforms, more C&D sorting, EfW, transfer stations and composting facilities to name a few.

Mixed (unsorted) waste represents over 90% of the materials sent to landfill. The highest priorities are organics processing (composting and anaerobic digestion below), mixed commercial waste sorting facilities and mixed demolition sorting facilities. Not difficult and well known. Other priority infrastructure includes glass sand manufacturing (from bottles), plastic reprocessing (in response to China see below), dirt reprocessing, consolidated well run landfills, community recycling centres and EfW facilities.

How do we pay for all this kit you say? The current landfill levies around Australia raise over $1.2b per year. Of that less than 20% is hypothecated to recycling and waste management (on average). There is an immediate source of revenue to build infrastructure.

Energy from Waste

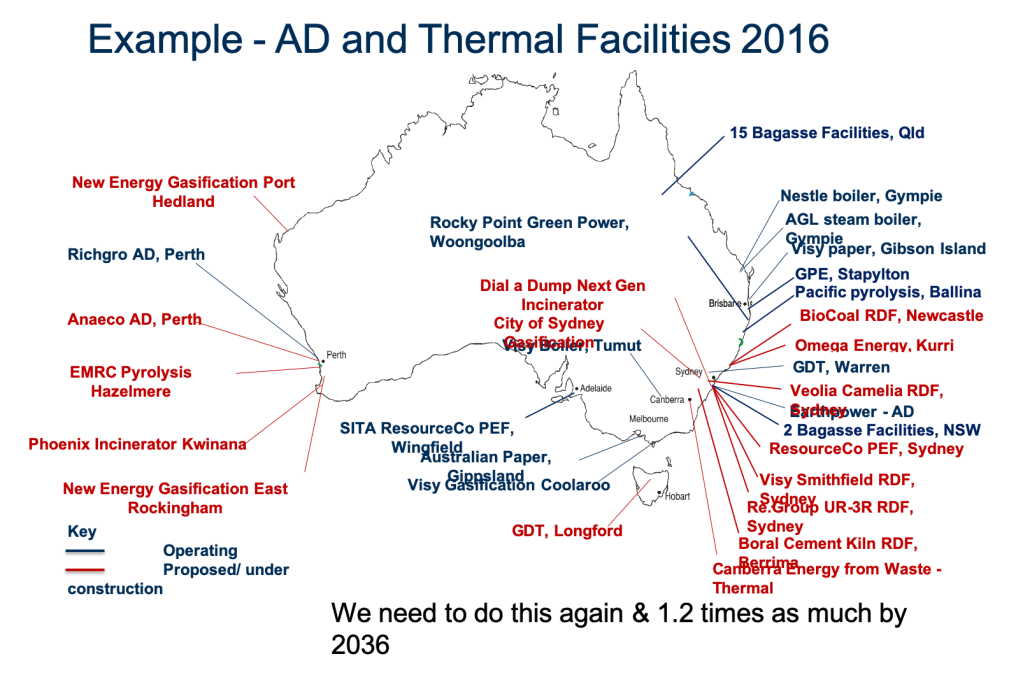

With QLD’s policy currently under discussion, all major States will soon have an EfW policy in place. No new facilities have been completed yet but that is about to change as construction recently began in WA’s Kwinana EfW facility while the Vic EPA has issued works approval to Australian Paper’s EfW. More are certain to follow, including PEF from C&I waste, complementing Australia’s 40 +biomass energy plants.

Properly done, EfW can progressively (over a 40-year time horizon) replace most landfills as the final disposal option for residual waste. We are seeing most State governments (with some notable exceptions) rolling out the following key policy settings:

- Don’t cannibalise recycling;

- Residual material only – no higher order value, i.e. the residual of the residual stream after processing it;

- Meet international air emission standards; and

- Generate power or heat (not just waste disposal).

It is reasonable to expect the above high standards from EfW facilities. And there is a strong argument that the same should apply to landfills, especially when it comes to specifying minimum recovery rates that apply to the supply chain feeding EfW. Being consistent would level the playing field for both of our final disposal options, landfill and EfW. And it would ensure neither becomes a final destination for recyclables.

Organics

Of the 21Mt that is currently landfilled over 10Mt is organics (food, garden waste, pallets, timber etc). Organics breaks down anaerobically in landfill to generate methane, a potent greenhouse gas. The release of this gas to the atmosphere currently contributes close to 3% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. The industry has done well in capturing much of the methane but not enough.

The best solution is to keep the organics out of landfill and instead turn it into compost and return it to farmers. Simple, I hear you say. Yes it is. But it is currently uneconomic for many councils and most restaurants, cafes etc. The solution is either to subsidise composting facility construction and operation, as well as the organics collection, or to ban organics to landfill, as Europe has done.

And of course, we should not forget that diversion from landfill is one of the cheapest global warming abatement options.

Responding to China and Asian demand

The China National Sword policy has restricted the export of plastic and fibre to China by limiting the acceptable contamination rates to less than 0.5% (down from 2 and 5%). China has its own middle class generating their own recyclables. Why keep importing it from the West when China can clean up its own environment by recycling locally generated materials? But it is a big challenge for Australia’s existing recycling infrastructure (primarily Materials Recovery Facilities, MRFs). It is almost impossible (and very expensive) to reduce contamination to 0.5% in a MRF.

I often hear people say we shouldn’t be exporting recyclables overseas in the first place. My response is we export iron ore, coal, sheep etc. Recyclables are just bales of plastic and fibre that are traded internationally. We export them because that derives the best return for the MRF operator and the cheapest price for council (saving money for you and I as ratepayers). That is not to excuse the inclusion of contamination nor to minimise the problems of pollution in the Asian economies.

Solving China National Sword and the flow on restrictions in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, India etc requires that Australia cleans up its exported materials and on-shore as much reprocessing as possible.

That means improving MRF operations (capital and labour) to reduce the contamination in exported materials, as a first step.

But more importantly we must establish domestic secondary reprocessing infrastructure to convert the materials to a cleaner secondary product. That means not exporting bales of PET containers or HDPE milk bottles but washing and pelletising them here so that we can export a clean plastic pellet. I hear you asking why we haven’t always done that. We haven’t for good economic reasons. It has always been cheaper and more efficient for the Asian business at the end of the transaction to do it (more automated processing at plastic and fibre mills, cheaper labour, etc). But not now. Now it is much more expensive to export any contaminated material and have it languish in shipping containers or worse still, be sent back. Australia must act and act quickly.

The Australian Council of Recyclers (ACOR) engaged MRA to undertake a cost benefit analysis of preferred solutions. For no more than $150m (once) our report said you could de-risk Australian recycling with three simple actions. Invest:

- $90m in infrastructure including local plastic, glass and fibre reprocessing as well as MRF upgrades;

- $30m in positive procurement program to build the markets for recycled content here in Australia (such as glass sand in road base and asphalt); and

- $30m in waste education to reduce gross contamination.

Where is the money going to come from I hear you ask? Again, landfill levies in Australia currently raise over $1.2b per year, every year. Paid by homeowners, businesses and the community generally to improve recycling and resource recovery. To de-risk Australian recycling in view of China’s National Sword and in the long term, the industry does not need much. Just over 10% in one year, once.

What does the Circular Economy really mean?

The idea of waste as a resource is an old one. It rejects the status quo “take-make-dispose” linear economy in favour of cycling biological and technical materials. However, although putting materials out for recycling is well accepted; reincorporating those materials into the productive economy has languished. Designing products so that, at the end of their life, their materials can be reincorporated into new products is even less common.

A circular economy goes beyond improving recycling; it aims to close the loop by influencing not just end of pipe recycling but also design, logistics and the entire value chain. A future where resources come from waste, where waste materials become feedstock for regenerative economies. A future of green collar jobs, of a densely integrated system of remanufacturing that sustains local industry.

The circular economy feels obvious, even overdue. The sort of thing that has been talked about for decades but still isn’t happening at scale. The key reason we do not have a circular economy is because recycling costs more money than cheap landfill disposal. Essentially, it is a “market failure” although economists will hesitate to describe it as such. Insofar as they consider the problem at all, they look at the decisions of each of the actors in the marketplace and consider these decisions to be rational.

Therefore, left to the market, the circular economy will not happen. Governments have to intervene and lead the way for a circular economy because the endpoint is an economy that is more valuable, creates more jobs, is healthier and most importantly, has significantly less impact on the environment. I would argue that fostering a circular economy is so important that it would be worth forming a Circular Economy Commission (akin to the Productivity Commission) that would look to untangle the thicket of obstacles that prevent the market from delivering on the benefits of a circular economy. Or at least, as proposed by ACOR, Australia’s Environment Ministers could agree to a National Circular Economy & Recycling Plan that invests in infrastructure, improvement and innovation.

Government procurement (see below) would be key in kickstarting a circular economy but to sustain it initiatives to encourage businesses to buy locally recycled products are also important. Moreover, in a truly circular economy, ease of recyclability would also dictate the demand for raw materials. So, the relatively easy to recycle PET and HDPE would ultimately displace harder to recycle polymers when it comes to product packaging.

Government procurement

In the absence of a circular economy, recycling infrastructure and kerbside collections, although important, are “end-of-pipe” solutions. And they have been extensively supported by some governments and sometimes resulting in an oversupply of (ex-waste) resources. A critical gap in our current resource recovery sector is now demand side purchasing. The recycling sector generates material for which there simply aren’t enough viable local markets.

With procurement in Australia being worth around $600 billion annually, and a large percentage of that being government procurement, the end markets for recycled plastics, metals, glass, paper, e-waste and tyres are there. They just need to be accessed.

Governments, as the largest purchasers of goods and services in the country, should lead by creating markets for recycled products and materials. Last year the Victorian government committed to a “recyclables first” procurement policy, essentially using its considerable purchasing power to drive demand for local recycled products. All governments should follow suit with even more ambitious targets. It is simple enough to turn the glass that is stockpiled around the country into sand for road building, plastic into furniture and railway sleepers, etc.

Extended Producer Responsibility

2018/19 saw the emergence of EPR schemes from the shadows. The rollout of Container Deposit Schemes in NSW, ACT, QLD and now WA (with SA and NT having schemes for years) has woken the public to waste management and litter in particular. In my view it is only a matter of time before Vic and Tasmania join the program. Consolidating eight different schemes into one management structure would make sense but is not a first order waste issue.

Extending EPR to other materials is a high priority. Mandatory EPR schemes for tyres, white goods, mattresses, old cars, oil, e-waste (computers and TV’s are already being done), solar panels, single use batteries, gas bottles, smoke alarms etc would do a lot to reduce illegal dumping and reduce the free-riding which plagues current voluntary schemes.

Better Data

The government released the National Waste Report 2018, covering 2016/17 data, in late 2018. The previous one (National Waste Report 2016) was released in 2017 and presented 2014/15 data. As a result, at a Commonwealth level, we are always working with numbers that are between two and four years old and that often includes interpolated data based on past numbers. In addition, the report recognises a number of data gaps and issues.

A lot of these issues stem from data problems at the State level. NSW’s recently released 2018 State of the Environment Report uses data that only goes up to 2015 and still excludes recycling data. In the best cases, States use data that are at least two years old.

Policy makers, generators, collectors and processors need good data. We can’t ask investors to stump up hundreds of millions of dollars on the back of old and inaccurate data. Expecting a State and National Waste Account within six months of the end of each financial year is not unreasonable.

We should also push for benchmarking across the board, especially for local government. That way, councils know who the leaders are and they know who to talk to for tips. Peer pressure and access to best practice will drive improvements.

Community Engagement

So far, on a State and Commonwealth level most community engagement has been on “iconic” waste streams (such as plastic bags and coffee cups). This engagement is easy and cheap; it appeals to people’s emotions and is generally magnified by the media for free.

However, it is also quite ineffective in terms of tonnes recycled or diversion from landfill. But engagement is important. High community participation is necessary in tackling big ticket items such as waste avoidance, organics recovery and to reduce contamination of the yellow kerbside bin. Usually, it is left to local governments to garner community support and provide waste education. A more streamlined approach on a State or Commonwealth level (from standardised bin colours and recyclable types accepted to education material) could go a long way towards streamlining community engagement, reducing its costs and increasing recovery.

Climate Change

I have often called out Climate Change for what it is, an existential threat and the greatest challenge of our time. I am also aware that Australia represents only 1.3% of global emissions. However, we are also one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with one of the highest per capita emissions profiles. Therefore, we need to get to the point where we accept some short term pain in order to reduce Australia’s emissions and to contribute meaningfully to international efforts.

The waste sector contributes 2.7% of Australia’s total emissions. Our waste industry has historically reduced its emissions more than virtually all other sectors. It’s now emitting about 12 million tonnes per annum, down from almost 16 million tonnes in 2000. That’s largely due to landfill gas capture and taking organics out of landfill. We are already punching above our weight but there is still much that can be done:

- better landfill gas capture and use;

- avoided landfill emissions by diverting waste containing degradable organic carbon;

- save energy by recycling the embodied energy of paper, cardboard, glass, steel and aluminium[2];

- use EfW to displace fossil fuels[3] and avoid emissions[4];

- convert suitable waste to biochar and apply to land (carbon capture and storage); and

- use new electric waste trucks or convert existing ones to use biogenic fuels to displace fossil fuels.

In all, the waste sector could reduce Australia’s emissions by around 58Mt or 10% of the country’s emissions. And all that at such a relatively low cost, that we should be doing it anyway.

Tweet

Conclusion

In my experience Australians care for the environment. When it comes to waste, most businesses and households support better recycling (even if it means more work at home to source separate) and somewhat higher landfill levies. However, they expect for most of the levy revenue to be hypothecated to recycling infrastructure and systems. With that sentiment in mind and a new Waste Minister at the Commonwealth level, we are on the right path. Recycling rates are rising, new technologies are emerging, infrastructure is being built and with it jobs and economic returns.

However, the fact is we are struggling to fully cope with the aftermath of China’s National Sword and we are massively underperforming relative to State Targets. Waste is politically simple. Few voters disagree with more and better recycling.

We need leadership from Government and we need it now.

As always, I welcome your feedback on this, or any other topic on ‘The Tipping Point‘.

[1] According to the Department of the Environment and Energy National Waste Report 2018, “In 2016/17, 21.7Mt of waste was deposited in landfill, comprising 40% of the 54Mt of core waste generated.” 2019 is likely to be the same.

[2] Capturing the embodied energy of recyclables going to landfill can provide at least 11Mt indirect abatement.

[3] EfW through coal substitution alone can add another 46.7Mt in CO2-e emissions savings.

[4] In 2015, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (2015), estimated that new EfW and biogas projects “could avoid 9 million tonnes of CO2-e each year by 2020, potentially contributing 12% of Australia’s national carbon abatement” http://www.cleanenergyfinancecorp.com.au/media/107567/the-australian-bioenergy-and-energy-from-waste-market-cefc-market-report.pdf

This article has been published by the following media outlets: