UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 – aspirational or achievable?

By Mike Ritchie – Director, MRA Consulting Group

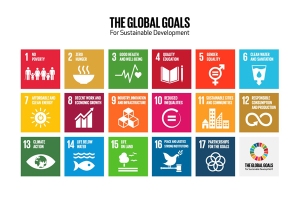

In September 2015 in New York, the 193 members of the United Nations (UN) member states agreed to the goals and objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2030 Agenda). The agreement outlines 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) across a range of significant global initiatives that will take us through to 2030 and beyond[i].

The reality is, that even though the Australian Government signed the agreement, we are not bound by it. In fact, the 2030 Agenda specifically states it is ‘non-binding’ and as such, goals and targets are, at best, aspirational.

The reality is, that even though the Australian Government signed the agreement, we are not bound by it. In fact, the 2030 Agenda specifically states it is ‘non-binding’ and as such, goals and targets are, at best, aspirational.

Each of the 17 goals are vitally important to the inhabitants of our planet. However, for Australia to achieve its commitment to the agreed goals, our government needs to immediately realign policy at every level to ensure they are not just inspirational stretch targets that can never really be achieved.

Goal 12 – Ensure sustainable production and consumption patterns has 11 targets which aims to do “more and better with less[ii]”. Amongst others, the targets include the need to halve food waste throughout the entire production, supply, retail and consumer chain within the next 15 years (goal 12.3) and focus on substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse (goal 12.5). Sounds great, however, current policy is not outlining ‘how’ these goals are achievable for Australia.

How does Australia shape up?

Recent ABS statistics show that in 2015, Australia’s natural wealth is valued at $5.8 trillion. In an Australian first, the research looks at how the country’s natural assets (such as forests, water and land) improve or deteriorate through economic activity. In terms of waste, the results are not good. The statistics show that waste generation grew by 163 per cent between 1996-197 and 2013-14[iii] and that for every dollar spent on economic activity, waste production increases by 50 percent![iv]

How can this be?

With countless programs available to drive waste reduction and improve resource recovery rates – waste levies, infrastructure and research funding, product stewardship, SME advice and funding support and residential education to name a few – there is still no specific national system that will ensure Australia’s success in achieving the global objectives.

In 2009, the National Waste Policy was agreed to by all Australian environment ministers and provides a strong framework and direction for waste management and resource recovery policies at all levels of government. That said, the policy only takes Australia to 2020. What about the following 10 years?

In NSW, the $70 million ‘Waste Less, Recycle More’ organics program, is attempting to tackle this issue by supporting programs that will “educate, expand collection and processing, increase food donation, and develop new markets[v]”. The underlying question is whether this initiative, and others like it, will deliver the agreed international outcomes.

Every state is tackling the issues in its own way. They all have different resource recovery and reuse programs funding projects that help improve kerbside collection services for food and garden waste, support new technologies and infrastructure, raise awareness of food waste, and develop new recycled organics markets. These programs all contribute in varying degrees towards achieving both our national and global commitments. Great! But with Australian households wasting around four times their own mass in food purchases each year (about 361kg per person annually), consumers also need to be forced to take responsibility of their purchasing habits and commercial enterprises (averaging 40 per cent or lower recycling rates[vi]) need to step up and be accountable for their products and service across the entire production and distribution chain.

What needs to be done?

Unlike the Tasmanian Dams Case back in the 1980’s, whereby constitutional law over-rode state law to achieve our international treaty obligations under the World Heritage Convention, Australia is under no obligation to achieve the targets set under the UN’s 2030 Agenda.

Whilst international governments, including our own, are required to accept ownership and institute effective national frameworks to achieve the SDGs, technically, we don’t actually have to do anything.

Addressing the requirements of the SDGs requires a clear and consistent approach to sustainability at all levels of government. Minister for the Environment, Hon. Greg Hunt MP, needs to secure the backing of the states to address the deficiencies of the current National Waste Policy and push-forward on the positives.

Federal, state and local government need to agree on a formalised commitment that will see national policies and processes tackle the big issues. Australia needs to adopt future-proof policies that challenge how we currently deal with the production and consumption of resources, material recovery and re-use, environmental management and investment in resource recovery infrastructure. We need to see strong consumer education platforms and increased pressure on corporations to support the ‘cradle-to-grave’ and beyond requirements of their products. These actions, amongst others, are essential now if there is any hope of Australia getting a pat on the back in 2030.

Conclusion

The government needs to outline exactly what strategies they have in place to implement and deliver on its ‘handshake agreement’ to the 2030 Agenda. It needs to look further than the next election and beyond the National Waste Policy 2020 objectives to specify exactly how we can achieve what other UN member states are already doing so well in our sector.

With the new ABS data, it is clear that there is much to be done at a federal level. As one of the leaders of the first world, Australia has great capacity to achieve the SDGs. There is much we can all do to improve our domestic situation and secure a sustainable future for generations to come. To do so, our Federal, State and Local government resource production, consumption, recovery, conservation and sustainability planning processes, policies and practices must be aligned.

Julie Bishop summed it up in her address at the 2015 UN Summit Plenary Meeting for Sustainable Development, “As United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has said, the true measure of success is not how much we promise but how much we deliver.[vii]”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

As always, I welcome your feedback on this, or any other topic on ‘The Tipping Point’.

[i] The SDGs replace the eight Millennium Development Goals that for the past 15 years, international governments have been working towards.

[ii] http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/

[iii] http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/mediareleasesbyCatalogue/D93FAC5FB44FBE1BCA257CAE000ED1AF?OpenDocument

[iv] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-04-15/abs-data-shows-growth-in-natural-assets/7327804

[v] http://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/wastegrants/organics-infrastructure.htm

[vi] https://blog.mraconsulting.com.au/2015/03/10/the-state-of-waste-2015/

[vii] http://foreignminister.gov.au/speeches/Pages/2015

This article has been published by the following media outlets: